HTTP Pipelining is an old optimization technique that’s been getting some renewed interest recently. I’ve written in the past about how pipelining is broadly used in Mobile, and recently Chrome & Firefox have been considering enabling it by default.

I set out to try and assess the value of pipelining for page load times, and surprisingly found it have very little effect. This result surprised me, so I dug deeper and looked at this data from multiple angles – the rest of this blog summarizes my research and findings.

Quick and Dirty Results

If you don’t have time to read through the details, here are the bottom line results:

- HTTP Pipelining doesn’t seem to make websites neither faster nor slower

- These results persist across different websites, network conditions and browsers

- I believe the main reasons for pages not being faster are: - Many different domains on a page (hence few requests are piped)

- Other front-end bottlenecks (e.g. blocking scripts)

This is fairly consistent with the findings I saw in my recent SPDY performance evaluation. I believe the same underlying reasons (many domains, other front-end bottlenecks) are holding back both protocol optimizations.

First Test – Firefox 13, Pipelining on/off, Varying network speeds

My initial assumption was that pipelining would provide the most value on high latency networks. To test that, I measured the top 500 US websites (from Alexa) with pipelining on and off. I performed the test using WebPageTest and the Firefox agent (by setting a firefox preference using a script). I ran the test simulating DSL, Cable and Fiber bandwidth, and using 2-4 different latency values for each. The numbers were also included in my 2012 Velocity presentation.

The results are shown in the graphs below, showing average load times with and without pipelining, per bandwidth. The X-Axis is the applied last-mile latency in milliseconds. As you can see, the graphs are practically the same. Regardless of the network conditions, using pipelining hardly changed the load times, for better or worse.

Pipelining Implementation Is Complicated

Pipelining, while conceptually simple, actually leaves a lot of room for implementation details. Last year I highlighted a few key implementation decisions. Here’s a refresh on a couple of them.

Server Support Detection: **Using pipelining requires a server that supports HTTP/1.1 and a persistent connection. Because of that, many browsers don’t pipe right away on a new connection. Instead, they send a single request, wait to see that the response is an HTTP/1.1 response with a keep-alive connection, and only start piping requests then. This means they **validate support per connection.

Other browsers, such as Opera, took the first keep-alive response from a server as an indication that all connections to this server would act the same. This approach of validating support per server is more error prone, but enables more pipelining use.

Request Distribution Model: If a browser has 4 requests, and wants to send them over two connections, how would they distribute the requests amongst the connections?

Some browsers use the “Fill First” approach, where they fill a pipe first. This means requests 1-2 will go on one connection, and requests 3-4 on another.

Others use the “Distribute First” approach, where requests are first spread over the connections. This means requests 1 & 3 will go on the first connection, and 2 & 4 on the second.

In addition to those two parameters, during my tests last year all browsers seemed to prefer opening a new connection to piping a request. This means pipelining only started when the max connection limit was hit.

Firefox 13 validates support per connection, and uses the “Fill First” approach, both of which are not ideal in my opinion. The folks at Mozilla seem to share this view, since the pipelining model was completely overhauled in Firefox 14, and further refined in Firefox 16. The new model is more complicated than the variables I mention above, but seems more promising than Firefox 13.

It’s kinda cool (for a web performance geek) to see these differences visualized in a waterfall chart. Here are the waterfall charts of Firefox 13 with pipelining on and Firefox 16 with pipelining on and off loading the about.com homepage.

| Firefox 16, No Pipelining | Firefox 13, With Pipelining | Firefox 16, With Pipelining |

| [](http://res.cloudinary.com/guypo-blog/image/upload/v1431082703/about-com-waterfall-ff16-no-pipe_axaoni.png) | [](http://res.cloudinary.com/guypo-blog/image/upload/v1431082704/about-com-waterfall-ff13-with-pipe_schx7n.png) | [](http://res.cloudinary.com/guypo-blog/image/upload/v1431082704/about-com-waterfall-ff16-with-pipe_bjdqbx.png) |

Chrome’s support of pipelining, enabled via a command line option, also uses a different implementation model. Therefore, it seemed useful to repeat my test with Firefox 16 and Chrome, to see if the results are different.

Second Test – Firefox 16 and Chrome tests

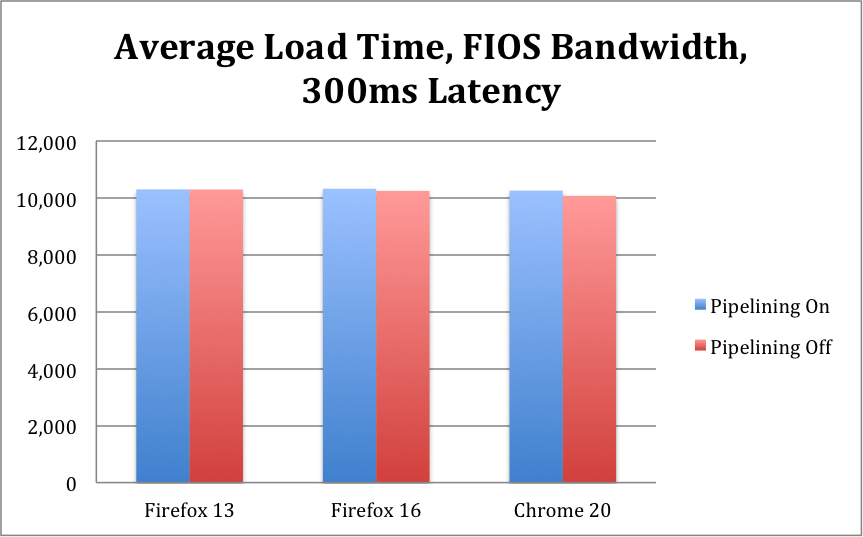

Due to some scale restrictions, my second test was a bit smaller. I loaded only the top 100 US websites, and only used Fiber bandwidth (20/5 Mbps down/up) and a 300ms latency. HTTP Pipelining should thrive under these conditions, since bandwidth is definitely not the bottleneck, and latency definitely is.

I ran the tests using Chrome 20, enabling pipelining with a command line (really using two separate agents), and with Firefox 16, enabling pipelining via a Firefox preference. Here are the results:

As you can see, the results are the same as before. Turning pipelining on didn’t make a material difference for better or worse in either browser. Both the average and median deltas were 1-2%, which is well within the margin of error.

It’s worth noting that Firefox 16 is still a “nightly” version, so it’s possible various bugs or missing features made pages load more slowly on it. However, as seen by the waterfalls before, the pipelining model has clearly changed.

Was pipelining even applied?

A valid question is whether pipelining even “kicked in”. On Firefox 13, since it prefers a new connection to a pipe and validates support per-connection, the first 12 (!!) requests on a domain are not piped. This means only domains with 13 requests or more benefit from pipelining.

Unfortunately, WebPageTest is not very Pipelining-friendly yet. In fact, it has a bug that leads to “missing” all piped requests. This bug means they don’t show up in the request counts or waterfall charts (by chance the response bytes count DOES show up in the total response size).

Luckily, we can use this bug to our advantage – we can look at the average number of requests with and without pipelining, and make that a (slightly hacky) estimate for how many requests were piped. Here’s a table with the number with the numbers per browser:

| **Browser** | **Requests (Pipelining Off) ** | **Requests (Pipelining On)** | **Estimated piped requests** |

| **Firefox 13** | 79 | 68 | 11 (13.9%) |

| **Firefox 16** | 78.6 | 65.9 | 12.7 (16.1%) |

| **Chrome** | 77.8 | 65 | 12.8 (16.4%) |

As you can see, pipelining was clearly applied, but only a small number of requests were piped, regardless of the browser. I’ll discuss why later in this post.

In addition to these numbers, I also did some manual spot-checking. I re-ran several tests manually and added network capture (tcpdump). I then downloaded these files and manually verified in Wireshark that pipelining was applied.

Third Test – Aggressive Pipelining in Firefox 16

The newer pipelining implementations in Firefox 16 and Chrome are actually more complicated than what simple synthetic measurements show. More specifically, browsers now have some learning components to them, and “remember” how servers in previous events, using pipelining more or less accordingly.

Firefox 16 offers a “brute force” setting that makes it use pipelining aggressively (network.http.pipelining.aggressive). This setting throws caution to the wind, pipes as much as it can, and uses fallback mechanisms if a problem occurs (e.g. the server closed the connection in the middle).

I reran the reran the test on the top 100 websites using Firefox 16 in “aggressive” pipelining mode, again using FIOS bandwidth and 300ms latency. The average results looked roughly the same, the average pipelining load time being 3% slower than not using pipelining – effectively the same. The median result was worse, showing pipelining to be 8% slower. Pipelining was definitely used more, with 35% of the requests being piped (on average).

The biggest impact, however, was the variance. Using aggressive pipelining made certain sites MUCH slower. For example, about.com was 2.5 times slower with aggressive pipelining. Other sites balanced this effect by being faster, with good results being 10-15% faster.

Using aggressive in this manner is probably not the smartest move, and the learning modes browsers employ would hopefully identify websites where pipelining causes harm, and not use pipelining for them. That said, even if you average the best pipelining result for each site (the lower load time with pipelining on or aggressive), pipelining only offers 1% acceleration over piping at all.

Why isn’t it faster?!

HTTP Pipelining should make websites faster. Especially on a high-bandwidth, high-latency network, logic implies pages should load faster. However, in all of these tests, I had a hard time proving that in real tests…

One possible explanation is “Head of Line Blocking”. This is the classic fear associated with pipelining, where slow resources hold up a queue, slowing down everyone behind them. It’s hard to automatically assess if head of line blocking occurred (perhaps better tooling in the future will make it possible), though perhaps the “aggressive” pipelining results hint that it affects the result. That said, based on some sampling of the results and my personal experience, I don’t believe this is the main reason pipelining isn’t faster.

**I believe pipelining didn’t make pages faster because we didn’t use it enough. **

In the non-aggressive case, less than a sixth of the requests on a page benefited from pipelining. In addition, some anecdotal checks show that even fewer requests for JS and CSS resources were piped, as a result of the implementation models and logic. Most of the piped requests were for images, which – per request – don’t impact page load time as much.

Even with a highly aggressive case, only a third of the requests were piped. When we piped more requests, we started seeing some websites that get a noticeable boost , hopefully browsers actually achieve those numbers through learning. If we could pipe more requests, applying pipelining intelligently, I’d expect the value to increase further.

There are three reasons I see for pipelining not coming into play:

- Too many domains on a page. In this test, a page had 18 different domains on average. Many of those domains only server 1-2 resources. Pipelining can’t optimize across domains, and doesn’t help domains with only a handful of resources.

- Other Front-End Bottlenecks. Pipelining doesn’t prevent delays caused by blocking scripts, CSS imports or 3rd party widgets. If these delays dominate the page load time, we can’t expect pipelining to have much effect.

- Implementation Details. Browser vendors fear head of line blocking and proxies that may break pipelining, and are therefore not quick to pipe. These are valid concerns, and currently the only way to use pipelining anyway is to make the browser learn where it can and can’t be used.

Summary

HTTP Pipelining, while it should help in theory, doesn’t seem to make browsing the web faster. The reasons vary, but simply put, the real web got in the way of a protocol optimization… Websites today are complicated beasts, network proxies don’t behave as they should, and accelerating in this context is not a simple feat. Subbu Allamar recently reached a similar a similar conclusion from his own set of tests.

One response to that could be to just use SPDY, with true multiplexing. However, SPDY requires SSL (which has performance costs), and does not address all bottlenecks either. Either way, in my opinion, these protocol optimizations will have little effect until we start building optimizations that accelerate across domains, and address front-end bottlenecks. Websites are not going to use less domains – domain sharding is still a good optimization on old browsers, and 3rd party widgets are being used more and more. Similarly, front-end bottlenecks will stick around until all web software is made perfect…

Making pipelining more effective won’t be easy, but I can offer two suggestions:

- Support piping requests to multiple domains on one connection. SPDY already does this for hosts that share an IP and certificate. If we can figure out how to validate a server is “allowed” to serve content for several domains, we can mitigate the impact of sharding and better leverage CDNs, which host multiple domains.

- Use Pipelining more aggressively, leveraging hints from the server. Much of the reason browsers “hold back” on using pipelining is not knowing what the server can handle. If the server could explicitly tell the browser to pipe more, browsers could do just that. Such hinting can be done using headers, using Mark Nottingham‘s “hinting” draft spec, or in other ways. Akamai made some HTTP/2.0 proposals of a similar nature.

Whatever the solution, we need pipelining implementors (and the entire team working on HTTP/2.0) new solutions to “think big”, or they’ll fall short.

If you’re interested in the full results of the tests, ping me via twitter (@guypod).