SPDY is awesome. It’s the first real upgrade to HTTP in 10+ years, it tackles high latency mobile networks performance issues and it makes the web more secure. SPDY is different than HTTP in many ways, but its primary value comes from being able to multiplex many requests/responses from client to server over a single (or few) TCP connections.

Previous benchmarks tout great benefits, ranging from making pages load 2x faster to making mobile sites 23% faster using SPDY and HTTPS than over clear HTTP. However, when testing real world sites I did not see any such gains. In fact, my tests showed SPDY is only marginally faster than HTTPS and is slower than HTTP.

Why? Simply put, SPDY makes HTTP better, but for most websites, HTTP is not the bottleneck.

The Bottom Line

If you don’t have time to read the full details, here’s the quick summary.

I tested the top 500 websites in the US (per Alexa), measuring their load time over HTTPS with and without SPDY, as well as over HTTP. I used a Chrome browser as a client, and proxied the sites through Cotendo to control whether SPDY is used. Note that all the tests – whether HTTP, HTTPS or SPDY – were proxied through Cotendo, to ensure we’re comparing apples to apples.

The results show SPDY, on average, is only about 4.5% faster than plain HTTPS, and is in fact about 3.4% slower than unencrypted HTTP. This means SPDY doesn’t make a material difference for page load times, and more specifically does not offset the price of switching to SSL.

I started this test because I found previous tests to be bad representations of the real world. This test is therefore different in several ways:

- I only enabled SPDY for 1st party content.

Website owners don’t control 3rd party domains and how they’re delivered. - I combined 1st party domains, but not 3rd party domains.

Most previous tests flattened the page into a single domain by creating static copies of pages, which is an artificial environment where SPDY thrives. - I did not use a client-side proxy, but rather reverse-proxied the website.

Using a client side proxy again creates one client/proxy connection where all requests are multiplexed, which is beneficial to SPDY but not realistic. - I tested real world websites, with all their warts.

This includes many domains on the page, unoptimized page, inefficient backends, etc. Most other data I’m aware of is either from the highly optimized Google websites or from static copies of websites, which eliminates many real world bottlenecks.

I’ll let you decide if these differences make it a better test or a worse test, but it helps understand why the results are different.

There could be many reasons why SPDY does not help, but the two that stand out are:

- Web pages use many different domains, and SPDY works per domain. This means SPDY can’t reduce connections or multiplex requests across the different domains (with some exceptions), and its value gets diminished.

- Web pages have other bottlenecks, which SPDY does not address.**For example, SPDY doesn’t prevent scripts from blocking downloads of other resources, nor does it make CSS not block rendering. SPDY is better than HTTP, but for most pages, HTTP is not the bottleneck.

The Test

For this experiment, I needed a set of websites to test, a client that supports SPDY and reverse-proxy that support SPDY.

For the websites, I chose the top 500 websites in the US, as defined by Alexa. The percentage of porn sites on that list is a bit alarming, but it’s a good representation of websites users browse often.

For a proxy, I used the Cotendo CDN (recently acquired by Akamai). Cotendo was one of the early adopters of SPDY, has production-grade SPDY support and high performance servers. Cotendo was used in three modes – HTTP, HTTPS and SPDY (meaning HTTPS+SPDY).

For a client, I used WebPageTest’s Chrome agent (with Pat Meenan’s help). WebPageTest automats a real Chrome browser (version 18 at the time of my tests), and through that supports SPDY. Note that Chrome randomly disables SPDY on 5% of browser runs, but WebPageTest disables this sampling. I measured each page 5 times, over 4 different network speeds, including Cable, DSL, low-latency mobile and high latency mobile.

Since some websites use multiple 1st party domains, I also used some Akamai rewriting capabilities to try and consolidate those domains. Roughly speaking, most resources statically referenced in the HTML were served through the page’s domain. This helped enable SPDY for those resources and consolidate some domains.

Lastly, since time of day and Internet events can skew results, I repeated the test 3 times, twice during the day and once overnight. In total I ran 90,000 individual page loads, or 30,000 per mode, more than enough for statistical accuracy.

The Results

The main result was that SPDY didn’t make the websites faster. Many different views of the data repeated this result:

- SPDY was only 4.5% faster than HTTPS on average

- SPDY was 3.4% slower than HTTP (without SSL) on average

- The median SPDY acceleration over HTTPS was 1.9%

- SPDY was faster than HTTPS in only 59% of the tests

- SPDY is only 2.1% faster than HTTPS when comparing the average load time of each URL/scheme, across batches and network speeds

- SPDY’s acceleration over HTTPS was 4.3%, 6.3% and 2.8% in each of the three test batches

When looking at individual network speeds, the numbers changed a bit but the conclusions did not. The following table summarizes SPDY’s impact compared to HTTP and HTTPS per network speed:

| **Network Speed (Down/Up Kbps, Latency ms)** | **SPDY vs HTTPS** | **SPDY vs HTTP** |

| **Cable (5,000/1,000, 28)** | SPDY 6.7% faster | SPDY 4.3% slower |

| **DSL (1,500/384,50)** | SPDY 4.4% faster | SPDY 0.7% slower |

| **Low-Latency Mobile (780/330,50)** | SPDY 3% faster | SPDY 3.4% slower |

| **High-Latency Mobile (780/330,200)** | SPDY 3.7% faster | SPDY 4.8% slower |

The exact numbers are not important, what matters is that they’re all small. No matter how you look at it, the conclusion is that SPDY doesn’t make a big difference.

If SPDY is better, why isn’t it faster?

The short answer is – it doesn’t fix the current bottlenecks. While digging through the data, I built up a couple of more detailed theories as to why it didn’t speed things up.

Too Many Domains

SPDY optimizes on a per-domain basis. In an extreme case where every resource is hosted on a different domain, SPDY doesn’t help. Web pages today use many different domains (most of them 3rd party domains), and thus keep SPDY from providing value.

The average web page (in this test) required resources from 18 different domains. Fewer than half of all resources were served from the same domain the HTML was fetched from. SPDY’s value comes primarily from reducing the number connections by multiplexing requests, and the large number of domains on a page keep that value from manifesting.

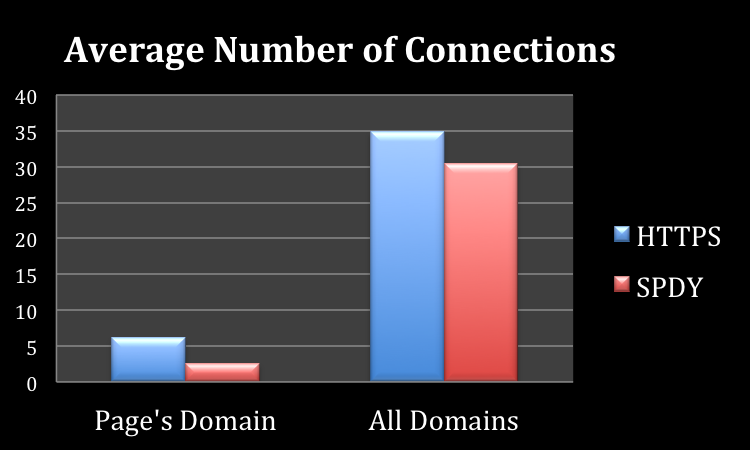

Looking at the individual tests, we can see SPDY cut the average number of connections to the page’s domain from 6.2 to 2.6* (compared to HTTPS) – a dramatic reduction. However, the total number of connections (includes all domains) averaged 34.9 for HTTPS and 30.5 for SPDY, which is similar in absolute numbers but not nearly as significant.

Even if all domains used SPDY, the results are unlikely to change. On average, 9 domains (out of 18) were used by one request only. 4 additional domains served 2 resources. Each such domain requires a TCP connection, and would not benefit from SPDY.

- Chrome seems to use one connection for the page, and a second for the resources. In some cases a late resource led to a third connection, or a random resource fetched from the non-SSL version of the site, raising the average to 2.6.

Blocking resources

Loading a page is not as simple as downloading all resources in parallel. For example, while loading a page, browsers usually don’t download any images until JavaScript and CSS files are fetched and processed. CSS files may import other CSS files, which the browser can’t know about in advance. Some scripts generate new resources for the browser to fetch.

These delays are not addressed by SPDY, and from all I can tell the related browser behavior has not changed. For many (if not most) pages, these delays are the true bottleneck, leaving little room for SPDY improvements.

Some Takeaways

There are two sets of takeaways you can draw from this study.

If you’re a website owner, the first thing you should do is adjust your expectations. Switching your site to SPDY will move you forward, but it will not make your site much faster. To get the most out of SPDY, you should work to reduce the number of domains on your page, and to address other front-end bottlenecks. Doing so is a good move anyway, so you wouldn’t be wasting your time.

If you’re a browser maker, or a participant in the SPDY community, you should put more effort into tackling these problems. For instance, Chrome already attempts to reduce connections by sharing the same connection across hosts that share the same IP and certificate. Certain changes to SPDY & SSL can further expand such reuse, thus accelerating pages and reducing server load. Another path is to build better SPDY awareness in the browser in an attempt to mitigate other bottlenecks. For instance, a more aggressive look-ahead behavior can download more resources up-front, and use request priorities to avoid congestion. To my knowledge, some of those concepts have been discussed, but none have been pushed forward yet.

I believe SPDY is still awesome, and is a step in the right direction. This study and its conclusions do not mean we should stop working on SPDY, but rather that we should work on it more, and make it even faster.